Elementary-particle detectors, 3D printed

An international collaboration headed by researchers in the Department of Physics has shown that additive manufacturing offers a realistic way to build large-scale plastic scintillator detectors for particle physics experiments.

In 2024, the T2K Collaboration started to collect new neutrino data following several upgrades to the experiment that included new types of detectors. One of these, called SuperFGD, has a mass of about 2 tons of sensitive volume and is made of approximately two million cubes. Each cube is made of plastic scintillator (PS) material that emits light when a charged particle passes through it. Neutrinos carry no charge, as their name indicates, but they sometimes interact with other particles, then producing electrons, protons, muons or pions that can be detected. Each PS cube is traversed by three orthogonal optical fibers that collect the scintillation light and guide it to 56’000 photodetectors. The data reveal three-dimensional (3D) particle tracks, which in turn allow researchers to learn more about neutrinos.

Detector upgrades of this kind are crucial to advance the discovery capabilities of large particle physics experiments, and yet it's fair to ask: what does it take to assemble, cube after cube and layer after layer, 2 million PS cubes into a functioning particle detector? Could large-scale detectors in high-energy physics be built differently? These are the questions that motivate one line of work of Professors Davide Sgalaberna and André Rubbia in the Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics. Together with colleagues from ETH Zurich, CERN, the HES-SO, the HEIG-VD, COMATEC-AddiPole and the Institute for Scintillation Materials in Ukraine, Sgalaberna and Rubbia have just published a research paper in the journal Communications Engineering where they present a fully additive-manufactured plastic scintillator detector for elementary particles. The authors are all part of the 3D printed DETector (3DET) Collaboration, which is led by Sgalaberna with the technical coordination of Dr Umut Kose. The team believes their demonstration to be a significant step in the direction of time- and cost-effective ways to build future large-scale particle detectors.

An engineering problem

PS detectors make it possible to track the paths and measure the energy loss of charged particles passing through the scintillator material with a fast temporal response. These characteristics have determined their growing success since they were proposed in the 1950s. In a PS, fluorescent emitters called fluors are introduced into a solid polymer matrix. A charged particle that propagates through the material excites the polymer matrix: a non-radiative dipole-dipole interaction transfers the excitation energy to the fluors, which de-excite by emitting near-ultraviolet light within few nanoseconds. A second type of fluor is often added to the polymer to shift the wavelength of the emitted light and avoid absorption in the scintillator material. Optical fibres collect the light produced by a PS by shifting its wavelength to the green part of the visible spectrum, making it possible to trap the emitted light and increase its attenuation length.

For optimal tracking of elementary particles, so-called granular 3D scintillating detectors have been assembled from many smaller volumes, such as the PS cubes in SuperFGD. In this scenario, it's crucial that the smaller units are optically isolated to track different charged particles independently. The 3DET Collaboration is familiar with these assembled detectors: Sgalaberna conceived SuperFGD and led its development and construction as a member of the T2K Collaboration. In the same way as the 2D screen of a laptop or smartphone is made of single fluorescing pixels, a granular 3D particle detector can be viewed as a collection of scintillating voxels. All voxels must work together to deliver high-quality data: each voxel is isolated but part of a bigger whole.

"This is really an engineering problem," says first author Tim Weber about the demonstration reported in the paper. Trained as a mechanical engineer at ETH Zurich, Weber joined the Exotic Matter and Neutrino Physics group in the Department of Physics and the 3DET Collaboration three years ago and brought in his diverse experience with additive manufacturing (AM), commonly known as 3D printing. He likes to take a pragmatic view on the matter: if the goal is to build ever larger particle detectors with excellent tracking resolution, the time and costs of production must be reduced. This calls for solutions that guarantee speed of production without compromising on the quality and performance of the particle detector.

The ideal production system can build thousands of scintillating voxels into a monolithic block. The 3DET Collaboration and others have already worked with AM for PS detector prototypes; some of the early challenges they encountered – especially in terms of detector performance – highlighted two crucial decision points: the choice of materials and the type of AM processes used to produce the detector. For example, AM is typically not great at handling multiple materials while achieving the material transparency needed for the scintillation light to not be reabsorbed by the PS. Additionally, not all AM processes can produce hollow structures. The latter issue often leads to subtractive interventions – drilling holes into the voxels for wavelength-shifting fibres, for instance – that make the fabrication procedure tricky to automate.

Custom-made solutions

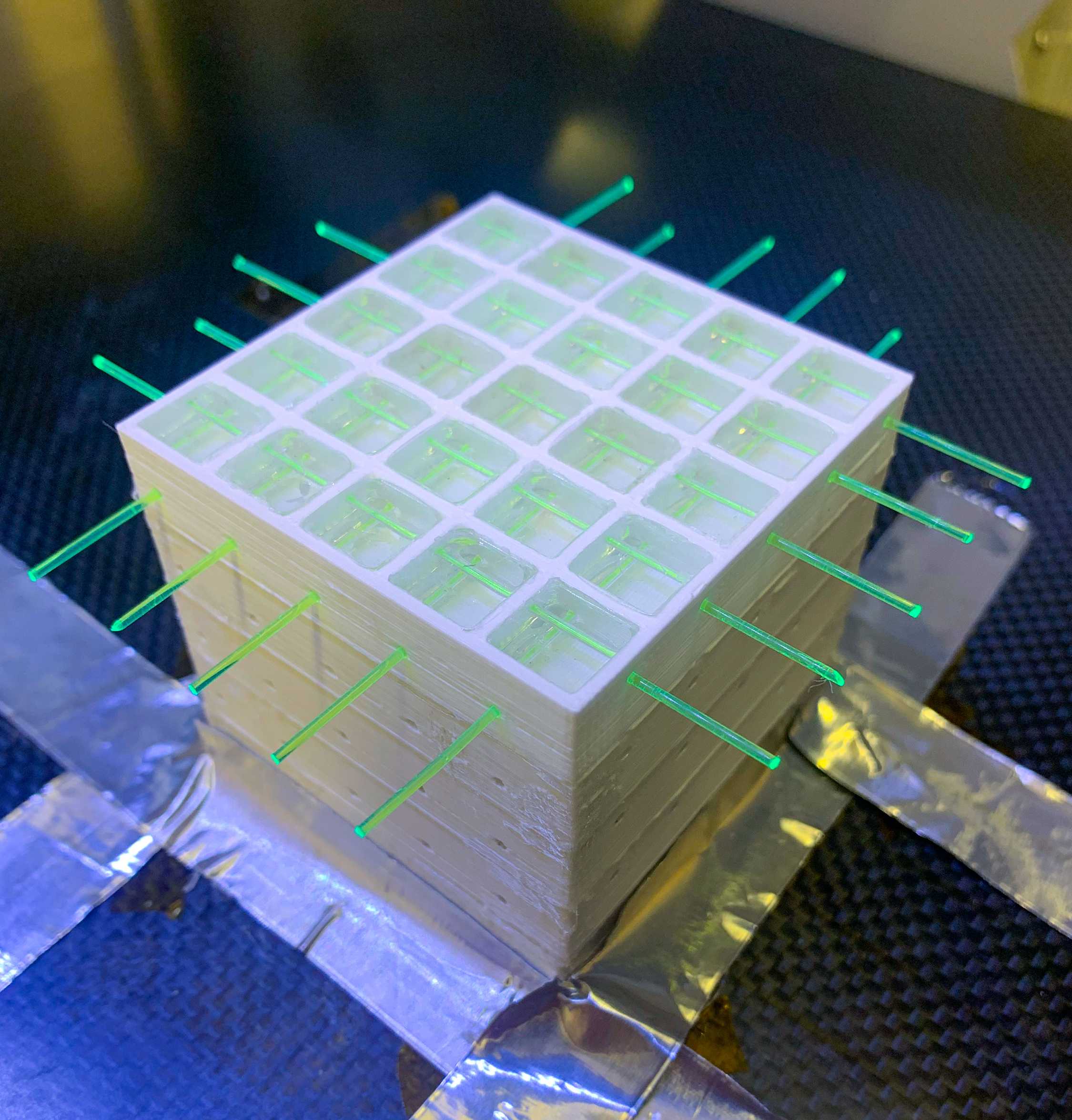

Weber, Sgalaberna and colleagues knew that they needed a fully customised AM setup. Their new manufacturing process, called fused injection modelling (FIM), is a mix of two known approaches, namely fused deposition modelling (FDM) and injection molding. The AM fabrication process counts three steps: first, a 5 × 5 layer of the optically reflective frame that creates the mold for the PS – that is, 25 empty cubes, top-opened and white-coated – is produced with FDM, including the holes for the optical fibres, without support structures. Here, the polymer string chosen for the frame is pushed through a nozzle in a process known as extrusion. Once this 5 × 5 mold is ready, metal rods are inserted into the holes to create space for the fibres. Then the FDM extrusion system is replaced with an elongated nozzle that injects scintillation material into the mold, moving from bottom to top in each empty cube and allowing the melted material to spread as evenly as possible. In the third step, a heated punch is used to ensure a plane top surface ready for the next 5 × 5 matrix layer.

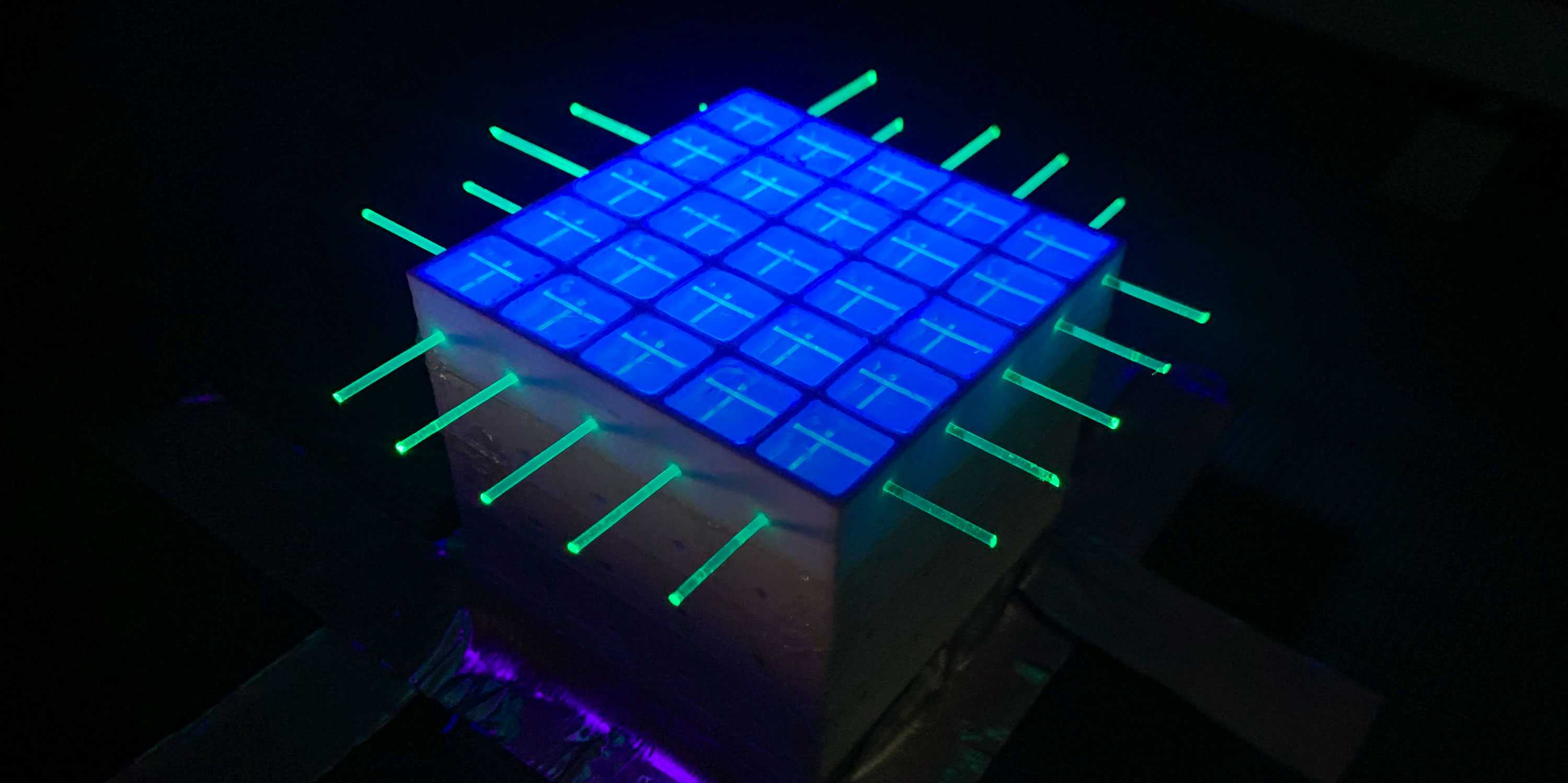

Following this procedure, the team fabricated what they refer to as a SuperCube, a detector counting 125 optically isolated voxels, arranged in a 5 × 5 × 5 configuration with overall dimensions of 59 mm (width and length) by 57.2 mm (height), where each voxel is read out by two orthogonal wavelength-shifting fibres. The manufacturing time for one voxel was estimated to be around 6 minutes: this time is expected to drop once the fabrication process is further automated thanks to a newly designed 3D printing system.

The researchers characterised the performance of their prototype with cosmic-particle data, focussing on the achieved single-cube scintillation light yield and the crosstalk between voxels. They compared the SuperCube to an analogous detection system produced with cast polymerisation, a conventional manufacturing technique, and found no significant deviation in performance. The crosstalk, which depends on the optical isolation of each voxel, appears to be slightly higher with FIM but is at the few-percent level, which is acceptable for particle tracking in 3D. "This is the first time a 3D printed scintillator detector is able to detect charged particles, such as those from cosmic rays and test beams at CERN, and reconstruct both their tracks and energy loss," says Sgalaberna.

The team has been testing new prototypes with the goal of optimising the optical isolation of the detector's voxels. At the same time, Weber is at work to redesign the entire production system: the goal is an automated printer that scales up the fabrication process to larger detector volumes. As Sgalaberna notes, going from a granular detector with 2 million voxels to one counting 10 million would represent a tremendous upgrade for experiments like T2K: the larger the detector volume, the more interaction events can be captured. It thus looks like 3D printing solutions may – quite literally – enable particle physics researchers to think big.

Reference

Weber, T. et al. Additive manufacturing of a 3D-segmented plastic scintillator detector for tracking and calorimetry of elementary particles. Commun. Eng. 4, 41 (2025). external page DOI:10.1038/s44172-025-00371-z