Watch those men on the moon

50 years ago today, the historic Apollo 11 mission came to an end. The teams in the NASA control centres had a clear view on the journey as it happened in part thanks to an ingenious invention by Fritz Fischer (1898–1947), ETH professor for technical physics: The Eidophor – a device to project TV images onto large screens.

The Apollo 11 mission – the first space flight to land humans on the moon – remains a milestone in the history of mankind. Countless factors contributed to the success of the mission, which ended 50 years ago today with the safe return of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins to Earth. Contributions came also from numerous Swiss companies, from the Araldit epoxy resins produced by Ciba to the Omega «moon watch», the Speedmaster (see this compilation on external page Swiss technology on the moon). A very visible role in the Apollo program had a device that originated at ETH, that was the leading product in its field for decades, but that has now largely disappeared from the scene. Eidophor projectors from Gretag AG in Regensdorf (canton of Zurich) were used to project data and TV images onto large screens at the NASA control centres in Cape Canaveral and Houston (see picture above).

An ingenious idea

The Eidophor method was invented by Swiss electrical engineer Fritz Fischer (1898–1947). Fischer studied electrical engineering at ETH Zurich from 1917 to 1924, before making significant contributions to various fields in the Telefonwerke Albisrieden and later at Siemens & Halske in Berlin, ranging from control systems for aircrafts and ships to processes for colour and sound film. In 1933, Fischer returned to Switzerland to teach and conduct research at ETH Zurich, where he also set up the Department of Industrial Research (Abteilung für industrielle Forschung, AFIF) at the Institute of Technical Physics. And here he developed the Eidophor method (the name is derived from the Greek word roots eido, 'image', and phor, 'bearer').

The idea was to project television pictures on surfaces the size of movie screens. Cathode-ray tubes are not suitable for this task, as they are not sufficiently bright. Therefore, in addition to the cathode ray, the Eidophor uses an arc lamp to deliver the luminosity needed. The image is generated by the cathode beam that draws the television image onto an electrically conductive oil film covering a rotating mirror. The electrical discharges cause slight deformation of the oil film, whereby the light of the arc lamp is scattered differently depending on location. As a result, the television image is reproduced by the reflection of the arc lamp.

The long path to success

The process was patented in 1939, and after a long period dedicated to development, a first prototype was put into operation in December 1943. That device was later replaced by a second prototype – a machine of proud size (see picture on the left), occupying two floors in the old physics building of ETH. Major contributors to the development came from Fischer's senior assistant Edgar Gretener, who after Fischer's early death in December 1947 further developed the Eidophor method in his own company, Dr. Ing. Edgar Gretener AG. But only after Gretener's own death in 1958 the Eidophor met commercial success (his company was by then renamed Gretag and taken over by Ciba).

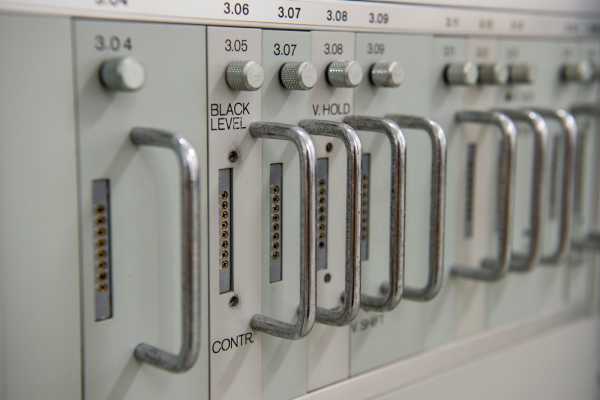

The systems were still massive, but compact enough to be transported and used in TV studios, sports stadiums and lecture halls. (Despite promising first steps, nothing came of the originally planned use in cinemas.) And the Eidophor also returned to the Department of Physics at ETH, which has meanwhile found a new home on the Hönggerberg. There it was used in lectures. Today, a device (an Eidophor EP 8) can be found in the basement of the HPH building – still in first-class condition, 25 years after its decommissioning (see photos below).

Use in space programmes

A highlight, not least for the Gretag marketing team, was the use of Eidophor systems by NASA, initially in the Apollo programme, but also in later programmes. The first steps on the Moon, as well as the way there and back, were displayed on 34 Eidophor screens at the NASA control contres (the devices are mentioned several times in the external page Apollo 11 Spacecraft Commentary). Those devices were adapted so that they could display 945 instead of 525 lines, as was the standard. NASA had made this request to be able to accommodate enough data on the image. And also the decision-makers in the Soviet Union appreciated the Eidophor systems, which were used as well in the Baikonur Cosmodrome in the Soviet space programme.

The Eidophor systems were finally replaced by newer technologies. But that does not detract from the fact that the success of the Eidophore underscores how a seemingly simple idea, meticulously implemented, can lead to unexpected applications. A large number of such ideas finally made, 50 years ago, something possible that still captures our awe and astonishment today.

Sources

ETHeritage Blog: Viel Licht für grosse Leinwände – Der Eidophor (2015).

C. Meyer. Der Eidophor: Ein Grossbildprojektionssystem zwischen Kino und Fernsehen 1939-1999 (Chronos-Verlag Zurich, 2009).

F. F. Betschon, S. Betschon, J. Lindecker. Ingenieure bauen die Schweiz: Technikgeschichte aus erster Hand (NZZ Libro Zurich, 2014).